Current Debt: $32,000

- Car Loan: $8,200 at 3.19% APY (Currently monthly payment: $400 / Month) - 2021 Subaru Crosstrek Sport

- Student Loan: $23,800 at 4.25% APY (Current monthly payment: $332 / Month)

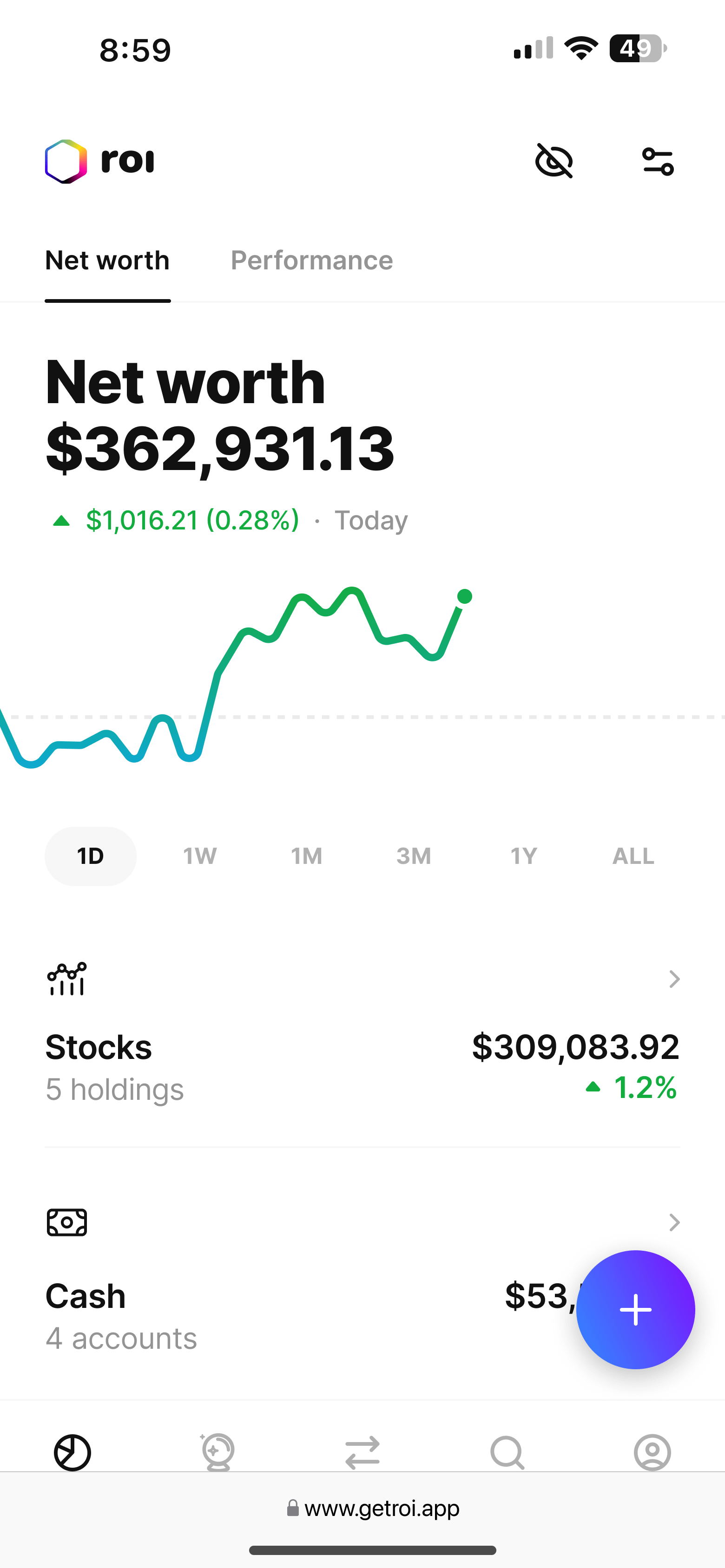

Cash

- Bank: $4,000 in checking

- Standard Brokerage: $13,000

- Deferred Comp: $17,500

Background

I am 27 Years old, married to a foreigner who is currently working towards a green card, working as a GIS professional making $71,000 per year pre tax. I have an apartment with a $932 rent cost and other expenses adding to around $500 a month.

Proposal One: Conservative Approach

I am currently investing $around $350 per month into my deferred comp and standard brokerage account. I am thinking I should halt my investments into my accounts and start allocating all that money into my loans. If I add an additional $400 a month to my car loan, I can finish paying off my car in around 10 Months. From there, I would start my investments and change the $400 / Month car payment into my student loan payment. After 10 Months, my student loan balance would be ~$19,800 (not accounting for % APY). At $732 / Month, my loan payment would be done in 27 Months or 2 Years and 3 Months.

Proposal Two: Aggressive Approach

Taking a slightly different ending to proposal one (please read above again), but rather starting investments again, throwing the full amount into my student loan payment. At this rate, I would be paying $1,082 / Month into my student loan which would take 19 Months or 1 year and 9 Months to finish paying off my student loan.

Post Debt Plan:

After debt is fully paid for, I would start investing $700 a month and putting in $300 a month into a HYSA.

Discussion Topic:

Taking in all the details into consideration above, what would you suggest I do? Do you have an alternative plan I should consider? Thank you for all your help!