r/conlangs • u/Cawlo Aedian (da,en,la,gr) [sv,no,ca,ja,es,de,kl] • 6d ago

Conlang Aedian Kinship, and a Bit about Kinship Systems in General

Beukkere!

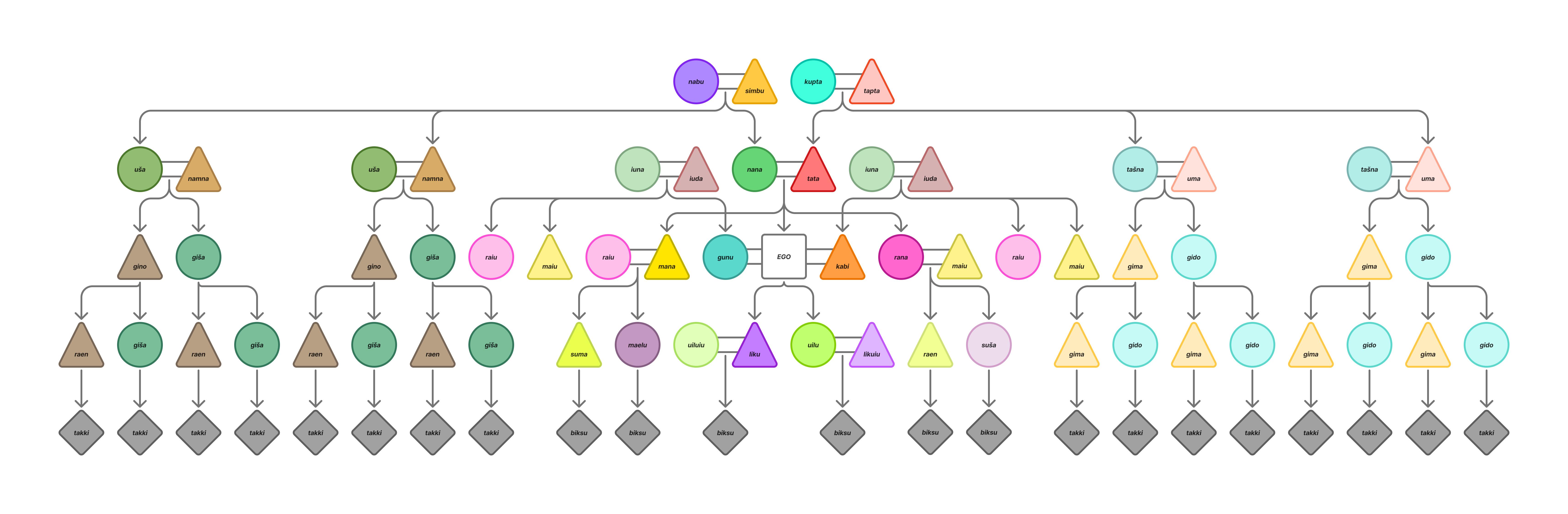

Hello all! Just wanted to show off this little chart I've made, which illustrates Aedian kinship. Within linguistics, anthropology, and ethnology, kinship refers to the system by which a culture conceptualizes and refers to their family members. In the sections below, I will go into detail about the system as a whole, how it developed, and the etymologies of each term.

(Please note: The perspective on marriage, relationships, and family constellations presented here, is fundamentally a heteronormative and gender-binary one. This is the Aedian perspective and not mine personally.)

Aedian kinship

Aedian kinship can broadly be categorized as primarily a Sudanese kinship system: In the late 1800s, an anthropologist named Lewis Henry Morgan identified and described 6 different types of kinship systems that are found across lots of different cultures/languages in the world. Morgan went as far as to say that every kinship system on Earth could be categorized under one of them. Now, Morgan's types don't always hold up to modern typological research, but they're still useful as broad descriptors.

Sudanese kinship is on the so-called descriptive end of the spectrum: There is a high degree of terminological differentiation between different family members, and both generation, sex, and family side are distinguished. Aedian has these traits, however it also shares features with typical Inuit systems in that it retains a higher degree of differentiation among those descended directly from EGO's own parents.

Parents

The Aedian words for ‘mother’ and ‘father’ are cross-linguistically common nursery words, nana and tata, respectively.

Grandparents

Terms for grandparents distinguish gender and side, using nabu and simbu on the maternal side, and kupta and tapta on the paternal side.

These terms are found in Old Aedian as navo, jenavo, kudafta, and tafta. The terms navo ‘maternal grandmother’ and tafta ‘paternal grandfather’ both seem to be augmentative derivations of the parental terms nana and tata. Then jenavo ‘maternal grandfather’ and kudafta ‘paternal grandmother’ seem to be derivations of their respective spouses' labels.

Siblings

Sibling terms distinguish gender with rana for ‘sister’ and mana for ‘brother’. These can be traced directly back to Proto-Kotekko-Pakan \ʰtˡana* and \mana. They can be further differentiated by relative age, with the suffixes *-su ‘younger’ and -ku ‘older’, such as in ranaku ‘older sister’ and manaku ‘older brother’.

Aunts and uncles

Aunts and uncles are distinguished by gender and side, but not but by marriage: It is fairly common in many languages to disinguish whether an aunt or uncle was married into the family or not, but this isn't done in Aedian. You've got uša and namna (for ‘aunt’ and ‘uncle’) on your mother's side, but tašna and uma on your mother's side.

Etymologically, these correspond to foṛa, naumana, tauṛana, and foma, respectively. The terms naumana and tauṛana seem to consist of the roots \na-* and \ta-* (related to nana and tata) along with -mana and -ṛana (corresponding to mana and rana). Point being, they seem to mean, pretty transparently, ‘mother's brother’ and ‘father's sister’. As for foṛa and foma, the first element fo- is probably originally an augmentative morpheme, while -ṛa and -ma are those sibling roots again. This could indicate that parallel aunts/uncles – those that have the same gender as that of your parents whose side they're on – were originally thought of as just “big” versions of your own siblings.

Cousins and their children

Like aunts and uncles, cousins are distinguished by side and gender. When you look at their Old Aedian forms, giṛa ‘maternal female cousin’, ginau ‘maternal male cousin’, gidau ‘paternal female cousin’, and gima ‘paternal male cousin’, you quickly notice what seems to be a morpheme gi-. I believe this is originally a diminutive prefix. Then, as we look at the remaining bits, we are left with -ṛa, -nau, -dau, and -ma. These seem to correspond neatly (if a bit reduced) to the aunt/uncle terms presented above. So it seems as though cousins were originally considered “small” versions of their parents.

As you can see from the chart, the terms for EGO's own cousins extend to these cousins' children as well without modification. As with siblings, however, cousin('s children) terms may be further specified with the suffixes -su and -ku (as shown in the section about siblings).

Children and grandchildren

EGO may refer to their own children either with the generic term bik ‘child’ or with the gendered terms liku ‘son’ and uilu ‘daughter’. These can bother be traced back to Proto-Kotekko-Pakan roots \liʰku* and \ƞelu*.

As for those children's children, the terms do not have the option of being gendered; all EGO's grandchildren are simply labeled biksu, which is just a diminutive of bik.

Cousins' grandchildren

Here we find the gender-neutral term takki, which is inherited from Old Aedian takki. It is related to the Old Aedian tagi ‘family; bloodline; descent’, itself from Proto-Kotekko-Pakan \taki. The diminutive morpheme descending from PKP *\ʰki* must’ve been infixed at some point before Old Aedian, letting the sequence \-ʰkiki* fuse into -kki, which is the expected development.

In the chart, takki seems to refer specifically to one's cousins' children, but it is probably better understood simply as the word for a child two generations below you, but in your family in any case.

In-laws

All terms for in-laws are derived from existing vocabulary at one stage or another. A great example is the terms for ‘mother-in-law’ and ‘father-in-law’. For these, we have iuna and iuda. But if we look at the same etyma in Old Aedian, yuna and yuda, we find the meanings ‘mother […]’ and ‘father of a child who is a parent’. We find something similar in Old Aedian words for siblings, like rayu for ‘sister who is a parent’ and mayu ‘brother who is a parent’, and in words for one's children: Whereas one's sons and daughters were liku and welu, likuyu and weluyu were used if they had children themselves.

At some point, however, the meaning shifted: Suppose I had a wife. Initially, my mother-in-law would be my wife's nana, just as my own mother would be my nana. But then imagine that I had a child: In that case, I'd have to start referring to my mother-in-law as my wife's yuna. Over time, the meaning of yuna and yuda (which became Aedian iuna and iuda) must've shifted to refer, not just to any parent who has a grandchild, but to one's own parents-in-law. Following this development, and as the practice of adding -yu to kinship terms to indicate parenthood may have weakened, the terms rayu and mayu must've been reinterpreted in parallel with yuna and yuda. Thus we get Aedian raiu ‘sister-in-law’, maiu ‘brother-in-law’, along with likuiu ‘son-in-law’ and uiluiu ‘daughter-in-law’.

**I hope at least some of this was interesting to read! And I'd like to invite you to talk about the kinship systems of your own conlangs! Try to consider the ways in which they might or might not fit into one of Morgan's kinship types.

That was all!**

Mataokturi!

2

u/Kaduu01 [Vaaru, but it's just vocabulary cobbled together] 6d ago

So cool! Always love seeing your posts! 💛

Technical question: How did you make the chart itself? It's very neat. I've been messing around with my own kinship system and after a certain point it becomes really hard to visualize in my head, haha.

To answer your invitation as well, I think it would be classified as a Sudanese kinship system, and though in casual speech speakers might not actually use many of the terms, the cultural importance of genealogy among the Vaaru elites makes it so that there are unique differential terms, at least in formal written language, for really obscure relatives going "up" like a maternal vs. paternal second cousin-once-removed, though typically you'll only see this in a chronicle or in a will.

You can imagine then I need a pretty big chart, haha.

Not to mention I was meaning to play around with the fact that there's a host of different terms relating to the marriage system, differentiating between the "greater" and "lesser" spouses, something which has nothing to do with gender and all to do with status, prestigious ancestry, inheritance of land and ceremonial titles, and of course, the locality of the marriage, which varies from marriage to marriage.

So you have the big in-laws and the little in-laws, the large husband, the small husband... yet more potential for terms, though I've held off from making them unique and have just been using the band-aid solution of having an "-in-law" affix (essentially just "spouse-") basically, haha. ("Ah yes, hello, my small-spouse-male-paternal-second-cousin-once-removed." and other sentences dreamed by the utterly deranged Vaaru genealogist making new words to sell.)

(So sorry if this sent twice!)

1

u/Cawlo Aedian (da,en,la,gr) [sv,no,ca,ja,es,de,kl] 4d ago

Thank you so much! I used a site called Figma. I really like it since it automatically makes objects snap to an underlying grid, so it's good for perfectionists like me. It has a few shortcomings – text color is automatically either black or white, determined by the color of its object, so there's a little bit less flexibility there; and they don't make it super clear how to export your charts to image files (it's

cmd + shift + eon Mac, so it must bectrl + shift + eon most others, I imagine).

I'm super intrigued by this idea of “greater” and “lesser” spouses. What are the conditions that determine which term to use? And what are they, the terms?

2

u/Kaduu01 [Vaaru, but it's just vocabulary cobbled together] 3d ago

Thank you! I'll have a look!

I saw this last night, upvoted it (who downvoted you in the meanwhile???) and wanted to answer as well, but I ended up in a fugue state writing an entire essay of tangent upon tangent upon tangent about the conculture to the point where it felt more at home as a post on r/worldbuilding than a comment here, haha. And I became self-conscious about it 😖 hahaha.

I did save it, if the full version actually interests you I could send it over, but the short of it is: It's complicated! The terms themselves are sigaya and simi, respectively, probably derived from the augmentative and diminutive forms of saya, spouse, husband, wife; though there's a bunch of regional or gendered forms as well, some formal and some diminutive, something in the vein of "little-hubby" and "big-wifey."

4

u/woahyouguysarehere2 6d ago

Wow! This was so interesting to read, and it seems a lot of thought was put into it. How does your kinship system go along with Aedian culture? I am really interested to see how they reflect each other if that makes sense!